The safeguards that Apple built into AirTags to prevent them from being used to track someone "just aren't sufficient," The Washington Post's Geoffrey Fowler said today in a report investigating how AirTags can be used for covert stalking.

Fowler planted an AirTag on himself and teamed up with a colleague to be pretend stalked, and he came to the conclusion that the AirTags are a "new means of inexpensive, effective stalking."

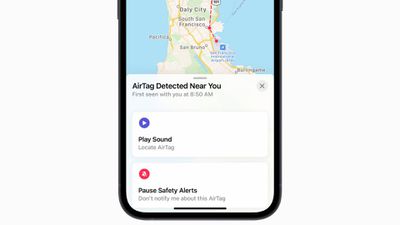

Apple's safeguards include privacy alerts to let iPhone users know that an unknown AirTag is traveling with them and may be in their belongings, along with regular sound alerts when an AirTag has been separated from its owner for three days.

Fowler said that over a week of tracking, he received alerts both from the hidden AirTag and from his iPhone. After three days, the AirTag being used to stalk Fowler played a sound, but it was "just 15 seconds of light chirping" that measured in at about 60 decibels. It played for 15 seconds at a time, went silent for several hours, then chirped for another 15 seconds, and it was easy to muffle by applying pressure to the top of the AirTag.

The three-day countdown timer resets after it comes in contact with the owner's iPhone, so if the person being stalked lives with their stalker, the sound might not ever activate.

Fowler also received regular alerts about an unknown AirTag moving with him from his iPhone, but pointed out those alerts aren't available to Android users. He also said that Apple does not provide enough help locating a nearby AirTag since it can only be tracked by sound, a feature that didn't often work.

I got multiple alerts: from the hidden AirTag and on my iPhone. But it wasn't hard to find ways an abusive partner could circumvent Apple's systems. To name one: The audible alarm only rang after three days -- and then it turned out to be just 15 seconds of light chirping. And another: While an iPhone alerted me that an unknown AirTag was moving with me, similar warnings aren't available for the roughly half of Americans who use Android phones.

The planted AirTag on Fowler kept his colleague well-updated with his location information, updating once every few minutes with a range of around half a block. While Fowler was at home, the AirTag reported his exact location, all using his own devices thanks to Apple's Find My network.

The Find My network is designed to make it easier to find a lost Apple device or item attached to an AirTag by utilizing hundreds of millions of active Apple products around the world. If you lose an AirTag and someone else's device picks it up, the lost AirTag's location is relayed back to you, and this also applies to AirTags tracking people.

Apple's vice president of iPhone marketing Kaiann Drance told The Washington Post that the safeguards built into the AirTags are an "industry-first, strong set of proactive deterrents." She went on to explain that AirTags anti-tracking measures can be bolstered over time. "It's a smart and tunable system, and we can continue improving the logic and timing so that we can improve the set of deterrents."

She also commented on some of the safeguards. Apple chose a three day timeline before an AirTag starts playing a sound because the company "wanted to balance how these alerts are going off in the environment as well as the unwanted tracking." Drance declined to say whether Apple had consulted domestic abuse experts when creating the AirTags, but she said that Apple is "open to hearing anything from those organizations."

Fowler admits that Apple has done more to prevent AirTags from being used for stalking than other Bluetooth tracking device competitors like Tile, but there are still concerns that need to be addressed. Fowler's full report that goes into more detail on how he mimicked being stalked and the shortcomings that he found in the AirTags can be found over at The Washington Post.